What will happen if you use a well-known and established in-memory key-value store as a persistent database (without TTL)? And what if it has been operated by a seemingly reliable and stable Kubernetes operator? And what if we make some “small and harmless” changes to the Redis configuration while adding more replicas? Well, we will try to answer the above questions in this article as well as review some utilities which will help you in optimizing the sizing of large Redis databases.

The problem

We use Redis within the Kubernetes cluster in various applications of our customers. Redis Operator by Spotahome helps us in managing and applying common practices within our company. In our experience, it is the most solid choice despite some problems, which we will discuss later in the article.

You may find the basic description of the operating logic of Redis Operator in the project’s documentation. Essentially, it creates a set of resources for running Redis failover that is based on the RedisFailover custom resource. This set consists of:

- ConfigMaps with Redis configuration;

- StatefulSets with Redis databases;

- A Deployment with the desired number of Sentinel replicas.

The specification in the RedisFailover resource allows you to:

- configure both the number of replicas and their requests/limits;

- customize pod configuration files (simple example);

- add persistence to Redis so that the data is kept not only in the case of deletion of Redis failovers but in the case of deletion of the whole Redis Operator as well (example);

- specify UID/GID used for running Redis containers (example).

By generating numerous RedisFailover resources, you can create and configure as many interconnected Redis failovers as you need.

Redis is being used as an in-memory data store, cache storage, and full-fledged stateful storage in one massive website consisting of several sub-projects. Because of that, the sizes of individual Redis installations have grown substantially. For example, the size of the .rdb file* of the largest Redis database in sub-projects has surpassed 5 Gb.

* The Redis database snapshot is one of two built-in options for saving the state to a hard drive.

Initially, we used the RedisFailover resource mentioned above with one Redis replica for this project. The instance was quite large and resource-demanding — it consumed around 16 Gb of RAM at the peak load (at the time of saving data to a disk). Any additional replicas simply did not fit the nodes.

Then, as resource consumption grew and subprojects moved to Kubernetes, new servers were added to the data centre. Thus, we have got the opportunity to increase the number of Redis replicas to two to improve the reliability of the database (given the importance of making Redis snapshots).

While increasing the number of replicas, we have decided to lower containers’ memory requests and limits from 22 GB to 19 GB since the resulting pods turned out to be excessively large (and we wanted to increase the probability of successful relocation to alternate nodes in case of a failure). Well, the decision to do this simultaneously with increasing the number of replicas has proven to be fatal.

We have prepared a backup for the rapid recovery and rolled out RedisFailover with the updated configuration. And here is what happened:

- StatefulSet expanded to two;

- the new instance became a slave, initiating a replication;

- shortly after that, the new instance was probed by the readiness probe (an ordinary ping is used for that!);

- because of this, Redis started updating the only pod with data (given that resources changed);

- sentinels instantly “realized” that master was absent and promoted an empty replica to the master (at that time, the master hardly managed to make the initial

BGSAVErequired for a full resynchronization); - after rolling update was over, the original replica connected to the recently promoted empty master;

- subsequent replication was instant, and it destroyed all the data.

The result is apparent: a total disaster (including downtime and the need to restore the data from a backup).

Since the Redis operator (its readiness probe, to be more precise) was the principal cause of what happened, we have created a relevant issue. While preparing/publishing this article, we got a response and a fix from developers and successfully tested it already.

So, the overall conclusion is that you have to be very careful when using Kubernetes operators for managing critical infrastructure components*. In the case of this specific Redis Operator, it has turned out that the configuration with a single replica is even more resilient to data loss than the one with multiple replicas. When new Redis nodes are spawned in the cluster, the system becomes unstable: the restart of the master node (for whatever reason) will inevitably result in a data loss (a flawed probe being the primary cause of that). Of course, before making any changes to the Redis cluster, you must back up the dump.rdb file.

* A small clarification for some concerns. We’re not assuming Kubernetes Operators themselves are bad. It’s all about how mature & well-tested they are simply because of being much more specific than core components. You should give a thorough evaluation of everything that goes into your production, and our case is quite illustrative in that.

Analyzing data

Well, we kept on going with our analyzing efforts. Given our hands-on experience gained while restoring this huge Redis cluster, we decided to analyze the data in the database.

Firstly, we run the latency doctor, a built-in Redis function, and got the following output:

127.0.0.1:6379> LATENCY doctor

Dave, I have observed latency spikes in this Redis instance. You don't mind talking about it, do you Dave?

1. command: 3 latency spikes (average 237ms, mean deviation 19ms, period 67.33 sec). Worst all time event 256ms.

I have a few advices for you:

- Check your Slow Log to understand what are the commands you are running which are too slow to execute. Please check http://redis.io/commands/slowlog for more information.

- Deleting, expiring or evicting (because of maxmemory policy) large objects is a blocking operation. If you have very large objects that are often deleted, expired, or evicted, try to fragment those objects into multiple smaller objects.

127.0.0.1:6379> LATENCY latest

1) 1) "fork"

2) (integer) 1574513316

3) (integer) 308

4) (integer) 308

2) 1) "command"

2) (integer) 1574513311

3) (integer) 214

4) (integer) 256As you can see, there are latency peaks in Redis related to executing fork and command. We assume that these peaks are associated precisely with the process of saving RDB file because of its size.

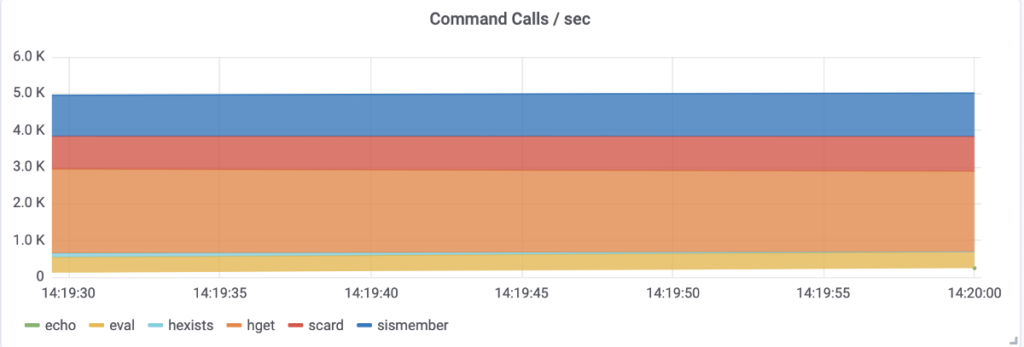

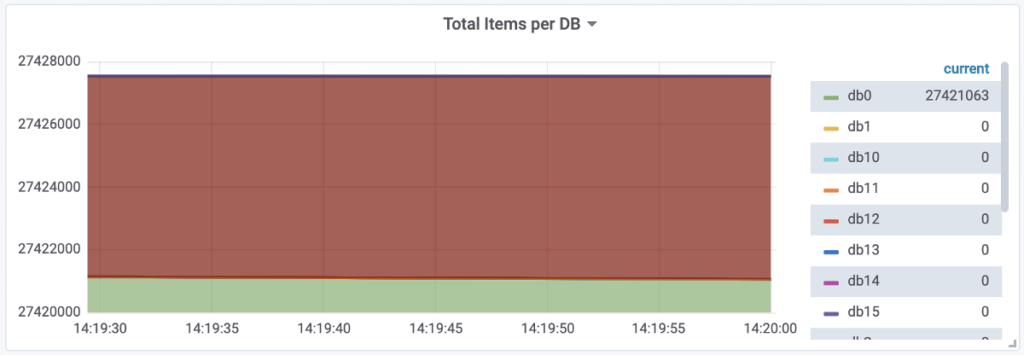

Grafana, which gets Redis metrics through Prometheus, shows the following picture:

The enormous size of the database and the high number of QPS are evident here.

Well, the next stage involves a more detailed study of Redis databases. We need an aggregate conclusion on how much space the databases occupy and how long they exist. We need to figure out what items can be deleted from the database and how to adjust the application code to avoid bloating the database. To do this, we directed our attention to existing Open Source tools. Here is a brief review of them based on our specific example.

1. Redis-memory-analyzer (RMA)

This Python-based tool is easily installed from PyPI using pip. We recommend running it on a separate (non-production) Kubernetes node or via a Redis Docker container (you first have to copy the dump.rdb file to its /data directory). Here is an example (docker-compose.yml):

redis:

container_name: redis

image: redis

ports:

- "127.0.0.1:6379:6379"

volumes:

- ./:/data

restart: alwaysNext, execute rma -f json on the node to get the output in JSON format (we believe it is more suitable for subsequent parsing than the plain text).

Below is the reduced and slightly obfuscated output for the most problem database:

{

"keys": [

{

"count": 16236021,

"name": "The:most:evil:set:*",

"percent": "59.24%",

"type": "set"

},

{

"count": 2463064,

"name": "likes:*:*",

"percent": "8.98%",

"type": "set"

},

{

"count": 2422160,

"name": "notifications:*",

"percent": "8.83%",

"type": "zset"

},

{

"count": 2102164,

"name": "YYY:*",

"percent": "7.67%",

"type": "set"

},

"nodes": [

{

"info": {

"active_defrag_running": 0,

"allocator_active": 16108007424,

"allocator_allocated": 16027311240,

"allocator_frag_bytes": 80696184,

"allocator_frag_ratio": 1.01,

"allocator_resident": 16336216064,

"allocator_rss_bytes": 228208640,

"allocator_rss_ratio": 1.01,

"lazyfree_pending_objects": 0,

"maxmemory": 0,

"maxmemory_human": "0B",

"maxmemory_policy": "noeviction",

"mem_allocator": "jemalloc-5.1.0",

"mem_aof_buffer": 0,

"mem_clients_normal": 49694,

"mem_clients_slaves": 0,

"mem_fragmentation_bytes": 308401864,

"mem_fragmentation_ratio": 1.02,

"mem_not_counted_for_evict": 0,

"mem_replication_backlog": 0,

"number_of_cached_scripts": 18,

"rss_overhead_bytes": -606208,

"rss_overhead_ratio": 1.0,

"total_system_memory": 67552931840,

"total_system_memory_human": "62.91G",

"used_memory": 16027240832,

"used_memory_dataset": 14661812642,

"used_memory_dataset_perc": "91.49%",

"used_memory_human": "14.93G",

"used_memory_lua": 1277952,

"used_memory_lua_human": "1.22M",

"used_memory_overhead": 1365428190,

"used_memory_peak": 16027625216,

"used_memory_peak_human": "14.93G",

"used_memory_peak_perc": "100.00%",

"used_memory_rss": 16335609856,

"used_memory_rss_human": "15.21G",

"used_memory_scripts": 35328,

"used_memory_scripts_human": "34.50K",

"used_memory_startup": 791264

},

"redisKeySpaceOverhead": null,

"totalKeys": 27402900,

"used": {

"active-defrag-max-scan-fields": "1000",

"hash-max-ziplist-entries": "512",

"hash-max-ziplist-value": "64",

"list-max-ziplist-size": "-2",

"proto-max-bulk-len": "536870912",

"set-max-intset-entries": "512",

"zset-max-ziplist-entries": "128",

"zset-max-ziplist-value": "64"

}

}

],

"stat": {

"hash": [

{

"Avg field count": 273.9381613257764,

"Count": 92806,

"Encoding": "ziplist [85.3%] / hashtable [14.6%]",

"Key mem": 127070103,

"Match": "YYY:*",

"Ratio": 4.11216105916338,

"Real": 1374780864,

"System": 899529088,

"TTL Avg.": -1,

"TTL Max": -1,

"TTL Min": -1,

"Total aligned": 2961700368,

"Total mem": 461390876,

"Value mem": 334320773

},

{

"Avg field count": 16.630734258229428,

"Count": 102498,

"Encoding": "ziplist [72.0%] / hashtable [27.9%]",

"Key mem": 51729452,

"Match": "ZZZ:*",

"Ratio": 3.4048548273474686,

"Real": 97797080,

"System": 63099024,

"TTL Avg.": -1,

"TTL Max": -1,

"TTL Min": -1,

"Total aligned": 265209096,

"Total mem": 80452286,

"Value mem": 28722834

},

{ … and so on … }When developers saw 'totalKeys': 27402900 and { 'count': 16236021, 'name': 'The:most:evil:set:*', 'percent': '59.24%', 'type': 'set' }, they grabbed their heads in amazement. Soon, they discovered flawed code, and at the time of writing this article, they were getting ready to clean up all Redis databases and deploy their fixes.

While we could stop our search for a perfect tool right away, we still have tried some other utilities. Let’s share our experience with them, too.

2. Redis-rdb-tools

Run pip install rdbtools python-lzf to install Redis-rdb-tools. You can use the same setup as for RMA and execute:

rdb -c memory dump.rdb --bytes 100 -f memory.csvBelow is the output:

database,type,key,size_in_bytes,encoding,num_elements,len_largest_element,expiry

0,sortedset,notification:user:50242,26844,skiplist,262,8,

0,set,zz:yy:35647,30692,hashtable,760,8,

0,set,pp:646064c2170c2e1d:item:a15671709071,39500,hashtable,319,64,

0,hash,comments:93250,7224,ziplist,353,15,

0,hash,comments2:90667,3715,ziplist,179,14,

0,sortedset,yy:94224,67972,skiplist,544,15,

0,hash,comments3:135049,70764,hashtable,1150,15,

0,hash,ll-date:2018-10-20 12:00:00:count,2043,ziplist,61,49,

0,set,likes:57513,2064,intset,498,8,

0,hash,ll-date:2018-09-29 04:00:00:summ,2091,ziplist,53,49,

0,hash,ll-date:2018-09-25 22:00:00:count,2243,ziplist,68,49,Overall, it is a decent tool capable of comparing specific RDB snapshots with each other and emitting Redis protocol where necessary.

However, we find it difficult to analyze its output since it requires additional parsing of results. The developers of the tool also created rdbtools.com, a paid GUI for visualizing Redis data. At the end of last year, it was discontinued (EOL), and its functionality was moved to Redis Labs (also in the form of a non-free product, RedisInsight). Such solutions are outside the scope of our article.

3. Redis-audit

The next tool is written in Ruby and a little outdated, to put it mildly. To install it, you have to copy GitHub repository, install Ruby and perform a couple of simple actions in the tool’s directory:

sudo apt-get install ruby-full

gem install bundler

bundle installRunning Redis-audit:

./redis-audit.rb -h 127.0.0.1In our case, it has had regular crashes with an error:

Auditing 127.0.0.1:6379 dbnum:0 sampling 50000 keys

Sampling 50000 keys...

5000 keys sampled - 10% complete - 2019-11-26 14:16:16 +0300

10000 keys sampled - 20% complete - 2019-11-26 14:16:18 +0300

./redis-audit.rb:144:in `delete': invalid byte sequence in US-ASCII (ArgumentError)

from ./redis-audit.rb:144:in `group_key'

from ./redis-audit.rb:130:in `audit_key'

from ./redis-audit.rb:99:in `block in audit_keys'

from ./redis-audit.rb:97:in `times'

from ./redis-audit.rb:97:in `audit_keys'

from ./redis-audit.rb:358:in `<main>'Since our resources were quite limited, we implemented a small workaround:

until ./redis-audit.rb -h 127.0.0.1 -s 50000 > dtf-audit; do echo "Try again"; sleep 1; done

Auditing 127.0.0.1:6379 dbnum:0 sampling 50000 keys

Sampling 50000 keys...

5000 keys sampled - 10% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:26 +0300

10000 keys sampled - 20% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:28 +0300

15000 keys sampled - 30% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:29 +0300

20000 keys sampled - 40% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:31 +0300

25000 keys sampled - 50% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:32 +0300

30000 keys sampled - 60% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:34 +0300

35000 keys sampled - 70% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:35 +0300

40000 keys sampled - 80% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:37 +0300

45000 keys sampled - 90% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:38 +0300

50000 keys sampled - 100% complete - 2019-11-24 22:18:40 +0300

DB has 27402893 keys

Sampled 6.25 MB of Redis memory

Found 90 key groups

==============================================================================It resulted into:

Found 107 key groups

==============================================================================

Found 1 keys containing strings, like:

ooo:04-01-2019

These keys use 0.0% of the total sampled memory (2 bytes)

None of these keys expire

Average last accessed time: 12 hours, 3 minutes, 22 seconds - (Max: 12 hours, 3 minutes, 22 seconds Min:12 hours, 3 minutes, 22 seconds)

==============================================================================

Found 1 keys containing sets, like:

ttt:fff:8aa26e6f8f7a232bd80877ddb4e3b7a4c7706be0031ab0a8f76adfb3e5448783

These keys use 0.0% of the total sampled memory (13 bytes)

None of these keys expire

Average last accessed time: 10 hours, 26 minutes, 34 seconds - (Max: 10 hours, 26 minutes, 34 seconds Min:10 hours, 26 minutes, 34 seconds)

==============================================================================

Found 1 keys containing hashs, like:

zz:yy:vv:b45c247c-bcc4ae1b-fdacd2da-471e6cba-b82b9a20-a32255df-caa95a8a-a2533c7c

These keys use 0.0% of the total sampled memory (24 bytes)

None of these keys expire

Average last accessed time: 11 hours, 46 minutes, 54 seconds - (Max: 11 hours, 46 minutes, 54 seconds Min:11 hours, 46 minutes, 54 seconds)It looks like you can get what you need, but first, you’ll have to deal with the error. Well, in our case (knowing the outcome thanks to RMA), that was a complete waste of time.

4. Redis-sampler

You can use the existing setup to run this utility written in Ruby. All you need is to download the script from the repository and run it with, say, a million samples:

./redis-sampler.rb 127.0.0.1 6379 0 1000000Its output is quite extensive:

Sampling 127.0.0.1:6379 DB:0 with 1000000 RANDOMKEYS

TYPES

=====

set: 864532 (86.45%) zset: 116538 (11.65%) hash: 16761 (1.68%)

string: 2055 (0.21%) list: 114 (0.01%)

EXPIRES

=======

unknown: 1000000 (100.00%)

Average: 0.00 Standard Deviation: 0.00

Min: 0 Max: 0

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

Note: 'unknown' expire means keys with no expire

STRINGS, SIZE OF VALUES

=======================

1: 1096 (53.33%) 4: 485 (23.60%) 5: 182 (8.86%)

6: 180 (8.76%) 7: 60 (2.92%) 3: 21 (1.02%)

2: 21 (1.02%) 342: 7 (0.34%) 8: 2 (0.10%)

32: 1 (0.05%)

Average: 3.89 Standard Deviation: 19.88

Min: 1 Max: 342

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 1: 1096 (53.33%) <= 4: 506 (24.62%) <= 8: 424 (20.63%)

<= 2: 21 (1.02%) <= 512: 7 (0.34%) <= 32: 1 (0.05%)

LISTS, NUMBER OF ELEMENTS

=========================

4: 86 (75.44%) 1: 14 (12.28%) 3: 7 (6.14%)

2: 7 (6.14%)

Average: 3.45 Standard Deviation: 1.05

Min: 1 Max: 4

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 4: 93 (81.58%) <= 1: 14 (12.28%) <= 2: 7 (6.14%)

LISTS, SIZE OF ELEMENTS

=======================

482: 2 (1.75%) 491: 2 (1.75%) 674: 2 (1.75%)

666: 2 (1.75%) 449: 2 (1.75%) 515: 2 (1.75%)

561: 2 (1.75%) 558: 2 (1.75%) 590: 2 (1.75%)

483: 2 (1.75%) 631: 2 (1.75%) 527: 2 (1.75%)

777: 2 (1.75%) 633: 1 (0.88%) 456: 1 (0.88%)

604: 1 (0.88%) 606: 1 (0.88%) 498: 1 (0.88%)

710: 1 (0.88%) 1946: 1 (0.88%) 481: 1 (0.88%)

(suppressed 80 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 70.18%)

Average: 699.10 Standard Deviation: 387.90

Min: 207 Max: 3686

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 1024: 72 (63.16%) <= 512: 30 (26.32%) <= 2048: 10 (8.77%)

<= 256: 1 (0.88%) <= 4096: 1 (0.88%)

SETS, NUMBER OF ELEMENTS

========================

1: 38506 (33.04%) 2: 20277 (17.40%) 3: 11991 (10.29%)

4: 7695 (6.60%) 5: 5456 (4.68%) 6: 4097 (3.52%)

7: 3171 (2.72%) 8: 2559 (2.20%) 9: 2112 (1.81%)

10: 1767 (1.52%) 11: 1527 (1.31%) 12: 1223 (1.05%)

13: 1060 (0.91%) 14: 1030 (0.88%) 15: 860 (0.74%)

16: 775 (0.67%) 17: 706 (0.61%) 18: 608 (0.52%)

19: 576 (0.49%) 21: 519 (0.45%) 20: 502 (0.43%)

(suppressed 924 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 8.17%)

Average: 2.89 Standard Deviation: 64.09

Min: 1 Max: 55774

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 2: 631053 (72.99%) <= 1: 186025 (21.52%) <= 4: 15631 (1.81%)

<= 8: 13305 (1.54%) <= 16: 8311 (0.96%) <= 32: 5008 (0.58%)

<= 64: 2845 (0.33%) <= 128: 1319 (0.15%) <= 256: 581 (0.07%)

<= 512: 282 (0.03%) <= 1024: 117 (0.01%) <= 2048: 35 (0.00%)

<= 4096: 16 (0.00%) <= 8192: 3 (0.00%) <= 65536: 1 (0.00%)

SETS, NUMBER OF ELEMENTS

========================

1: 38506 (33.04%) 2: 20277 (17.40%) 3: 11991 (10.29%)

4: 7695 (6.60%) 5: 5456 (4.68%) 6: 4097 (3.52%)

7: 3171 (2.72%) 8: 2559 (2.20%) 9: 2112 (1.81%)

10: 1767 (1.52%) 11: 1527 (1.31%) 12: 1223 (1.05%)

13: 1060 (0.91%) 14: 1030 (0.88%) 15: 860 (0.74%)

16: 775 (0.67%) 17: 706 (0.61%) 18: 608 (0.52%)

19: 576 (0.49%) 21: 519 (0.45%) 20: 502 (0.43%)

(suppressed 924 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 8.17%)

Average: 2.89 Standard Deviation: 64.09

Min: 1 Max: 55774

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 2: 631053 (72.99%) <= 1: 186025 (21.52%) <= 4: 15631 (1.81%)

<= 8: 13305 (1.54%) <= 16: 8311 (0.96%) <= 32: 5008 (0.58%)

<= 64: 2845 (0.33%) <= 128: 1319 (0.15%) <= 256: 581 (0.07%)

<= 512: 282 (0.03%) <= 1024: 117 (0.01%) <= 2048: 35 (0.00%)

<= 4096: 16 (0.00%) <= 8192: 3 (0.00%) <= 65536: 1 (0.00%)

SETS, SIZE OF ELEMENTS

======================

41: 250500 (28.98%) 32: 215070 (24.88%) 33: 142136 (16.44%)

5: 71140 (8.23%) 37: 54151 (6.26%) 40: 45521 (5.27%)

31: 28938 (3.35%) 36: 18885 (2.18%) 6: 18383 (2.13%)

4: 9766 (1.13%) 30: 2513 (0.29%) 44: 1967 (0.23%)

35: 1025 (0.12%) 3: 729 (0.08%) 43: 387 (0.04%)

26: 372 (0.04%) 34: 334 (0.04%) 8: 318 (0.04%)

29: 242 (0.03%) 71: 233 (0.03%) 28: 224 (0.03%)

(suppressed 129 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 0.20%)

Average: 32.53 Standard Deviation: 10.91

Min: 1 Max: 151

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 64: 515245 (59.60%) <= 32: 247497 (28.63%) <= 8: 90055 (10.42%)

<= 4: 10495 (1.21%) <= 128: 966 (0.11%) <= 2: 100 (0.01%)

<= 256: 76 (0.01%) <= 16: 50 (0.01%) <= 1: 48 (0.01%)

SORTED SETS, NUMBER OF ELEMENTS

===============================

1: 38506 (33.04%) 2: 20277 (17.40%) 3: 11991 (10.29%)

4: 7695 (6.60%) 5: 5456 (4.68%) 6: 4097 (3.52%)

7: 3171 (2.72%) 8: 2559 (2.20%) 9: 2112 (1.81%)

10: 1767 (1.52%) 11: 1527 (1.31%) 12: 1223 (1.05%)

13: 1060 (0.91%) 14: 1030 (0.88%) 15: 860 (0.74%)

16: 775 (0.67%) 17: 706 (0.61%) 18: 608 (0.52%)

19: 576 (0.49%) 21: 519 (0.45%) 20: 502 (0.43%)

(suppressed 924 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 8.17%)

Average: 23.62 Standard Deviation: 374.23

Min: 1 Max: 33340

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 1: 38506 (33.04%) <= 2: 20277 (17.40%) <= 4: 19686 (16.89%)

<= 8: 15283 (13.11%) <= 16: 10354 (8.88%) <= 32: 6220 (5.34%)

<= 64: 3085 (2.65%) <= 128: 1445 (1.24%) <= 256: 702 (0.60%)

<= 512: 388 (0.33%) <= 1024: 235 (0.20%) <= 2048: 148 (0.13%)

<= 4096: 107 (0.09%) <= 8192: 57 (0.05%) <= 16384: 31 (0.03%)

<= 32768: 13 (0.01%) <= 65536: 1 (0.00%)

SORTED SETS, SIZE OF ELEMENTS

=============================

7: 52226 (44.81%) 8: 45833 (39.33%) 6: 8702 (7.47%)

15: 2971 (2.55%) 5: 2896 (2.49%) 4: 484 (0.42%)

18: 448 (0.38%) 21: 445 (0.38%) 16: 348 (0.30%)

20: 274 (0.24%) 12: 272 (0.23%) 22: 227 (0.19%)

14: 204 (0.18%) 13: 191 (0.16%) 17: 150 (0.13%)

10: 94 (0.08%) 11: 71 (0.06%) 3: 37 (0.03%)

9: 36 (0.03%) 19: 26 (0.02%) 2: 21 (0.02%)

(suppressed 188 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 0.50%)

Average: 9.16 Standard Deviation: 22.30

Min: 1 Max: 722

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 8: 109657 (94.10%) <= 16: 4187 (3.59%) <= 32: 1610 (1.38%)

<= 4: 521 (0.45%) <= 512: 489 (0.42%) <= 128: 30 (0.03%)

<= 2: 21 (0.02%) <= 64: 13 (0.01%) <= 256: 5 (0.00%)

<= 1024: 3 (0.00%) <= 1: 2 (0.00%)

HASHES, NUMBER OF FIELDS

========================

1: 3261 (19.46%) 3: 2763 (16.48%) 2: 1521 (9.07%)

4: 1361 (8.12%) 5: 1289 (7.69%) 6: 611 (3.65%)

7: 238 (1.42%) 8: 236 (1.41%) 18: 173 (1.03%)

9: 173 (1.03%) 16: 160 (0.95%) 12: 160 (0.95%)

13: 158 (0.94%) 15: 157 (0.94%) 17: 157 (0.94%)

10: 155 (0.92%) 14: 154 (0.92%) 22: 141 (0.84%)

11: 140 (0.84%) 20: 137 (0.82%) 19: 123 (0.73%)

(suppressed 830 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 20.84%)

Average: 71.88 Standard Deviation: 397.44

Min: 1 Max: 10869

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 4: 4124 (24.60%) <= 1: 3261 (19.46%) <= 8: 2374 (14.16%)

<= 2: 1521 (9.07%) <= 32: 1418 (8.46%) <= 64: 1329 (7.93%)

<= 16: 1257 (7.50%) <= 128: 429 (2.56%) <= 512: 274 (1.63%)

<= 256: 238 (1.42%) <= 1024: 236 (1.41%) <= 2048: 181 (1.08%)

<= 4096: 84 (0.50%) <= 8192: 29 (0.17%) <= 16384: 6 (0.04%)

HASHES, SIZE OF FIELDS

======================

unknown: 13916 (83.03%) 5: 1570 (9.37%) 24: 244 (1.46%)

32: 225 (1.34%) 22: 127 (0.76%) 29: 86 (0.51%)

43: 82 (0.49%) 26: 60 (0.36%) 25: 47 (0.28%)

30: 42 (0.25%) 27: 41 (0.24%) 12: 40 (0.24%)

36: 34 (0.20%) 23: 34 (0.20%) 39: 31 (0.18%)

21: 23 (0.14%) 8: 23 (0.14%) 28: 17 (0.10%)

34: 15 (0.09%) 16: 15 (0.09%) 64: 15 (0.09%)

(suppressed 19 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 0.44%)

Average: 15.12 Standard Deviation: 12.77

Min: 2 Max: 64

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 8: 1600 (56.24%) <= 32: 969 (34.06%) <= 64: 201 (7.07%)

<= 16: 59 (2.07%) <= 4: 15 (0.53%) <= 2: 1 (0.04%)

HASHES, SIZE OF VALUES

======================

unknown: 13916 (83.03%) 13: 768 (4.58%) 14: 624 (3.72%)

6: 394 (2.35%) 12: 192 (1.15%) 3: 172 (1.03%)

4: 153 (0.91%) 7: 119 (0.71%) 2: 98 (0.58%)

5: 90 (0.54%) 21: 75 (0.45%) 20: 57 (0.34%)

16: 33 (0.20%) 1: 30 (0.18%) 15: 18 (0.11%)

9: 12 (0.07%) 22: 3 (0.02%) 19: 2 (0.01%)

8: 2 (0.01%) 71: 1 (0.01%) 32: 1 (0.01%)

(suppressed 1 items with perc < 0.5% for a total of 0.01%)

Average: 10.52 Standard Deviation: 5.05

Min: 1 Max: 71

Powers of two distribution: (NOTE <= p means: p/2 < x <= p)

<= 16: 1647 (57.89%) <= 8: 605 (21.27%) <= 4: 325 (11.42%)

<= 32: 138 (4.85%) <= 2: 98 (3.44%) <= 1: 30 (1.05%)

<= 128: 1 (0.04%) <= 64: 1 (0.04%)It shows the distribution by the object type in the Redis database based on a million samples. However, that does not help us a lot in our specific task.

5. RedisDesktop

This utility is an elementary GUI for Redis. It does have the memory analysis feature, however, when we run it on a fairly powerful laptop (with 32 Gb of RAM), it crashes all the time. We preferred not to delve into details since we have found another solution already, and the presence of a GUI isn’t the major selling point for us.

6. Harvest

This tool, written in Go, is extremely easy to deploy and run:

# docker run --link redis:redis -it --rm 31z4/harvest redis://redis

t:: 12.65% (697)

tl:i:n:: 10.75% (592)

tl:i:n:1: 5.68% (313)

t:n:: 1.91% (105)

t:n:i:: 1.87% (103)

c: 1.63% (90)

c:: 1.60% (88)

n:: 1.52% (84)

n:f:: 1.49% (82)

c:l:: 1.34% (74)Let’s try it with the number of samples that exceeds the number of keys in the database:

# docker run --link redis:redis -it --rm 31z4/harvest redis://redis -s 3000000

warning: database size (27402892) is less than the number of samples (30000000)

t: 6.35% (20471794)

tl:: 6.35% (20471508)

tl:i:: 5.52% (17777810)

tl:i:n:: 5.52% (17777693)

tl:i:n:1: 2.89% (9302664)

c: 1.06% (3398834)

c:: 1.02% (3297466)

c:c:: 0.84% (2697278)

tl:n:: 0.84% (2693697)

tl:n:i:: 0.82% (2649015)We were quite surprised since increasing the number of samples leads to a growing number of results. Harvest does not aggregate the output. Therefore, you need some additional tools (or a detailed aggregation expression) to analyze its results. In short, Harvest doesn’t quite fit us.

Analysis summary

We mainly relied on the RMA (redis-memory-analyzer) tool in our analysis. It provides the easiest way to obtain output that is also nicely suited for reading/comprehending. The developers discovered over 18 million excessive keys using our results. Supposedly, they were generated because of the wrong architectural solution in the application (it will be fixed later). For our part, we hope that databases will lose some of their “weight”, speeding up customer’s applications and improving their throughput.

Conclusion

The “classic” Redis cluster was the main character of this article. In essence, it consists of Sentinel, Redis master, and Redis slave. We decided not to use the Redis Enterprise Operator because of its opaque pricing policy, and the operator by Amadeus IT Group due to lack of maturity.

We haven’t considered schemes involving built-in clusterization, sharding, and failover in the article since they require additional resources and redesigning the code. However, now we can move in this direction using our findings. Since we were able to save resources, the built-in clusterization and sharding in Redis have become more relevant, and we consider them essential future steps.

Regarding the operator by Spotahome, we plan to reconsider its use after analyzing the situation. Of the tools reviewed, we think that RMA is the best option. It is the simplest, efficient, and most intuitive utility for a quick analysis of Redis databases. RMA helped us to effortlessly find out why did the Redis database grow so large and where to focus our efforts in code redesigning. Other tools required much more effort to get the same result.

* Redis is a registered trademark of Redis Ltd. Any rights therein are reserved to Redis Ltd. Any use by Palark GmbH is for referential purposes only and does not indicate any sponsorship, endorsement or affiliation between Redis and Palark GmbH.

Thanks for this amazing article.

Did you try using the redis-operator by opstree solution? according to my research I couldn’t find any redis operator that are open source we can rely on. Redis-cluster provided by bitnami seemed to look better.

My concern was existing redis operators didn’t provide any autoscaling and backup and restoring features (correct me if i am wrong) and this operator doesn’t seem to get any future updates?

https://github.com/spotahome/redis-operator/issues/677#issue-2003863791

what would i miss if i don’t use the operator thank you!

Hi,

Will you say that real Redis Cluster is the way to go and leave single Master + Sentinel? We are looking into running on Kubernetes and have live Redis when we upgrade cluster or Redis needs to move from node to node?

Hi Nikolaj! In most of our cases today, Redis Cluster is a rare bird. Mostly, we rely on Redis Sentinel and the above-mentioned Redis operator from Spotahome — despite this old issue described in the article, it still works well for us. If Redis’ performance is not enough, we substitute it with KeyDB — this transition can be done on the fly using the operator.

Hi Dimitry,

I am also evaluating Spotahome redis operator. Do I need to compile the source code (using make) or just deploy the operator using the yaml file they provided (in their example folder). I am new to it so want to get some advice. thank you.

Hi William! You don’t need to compile anything. Usually, you install Kubernetes operators using charts (via

helm install) or YAML manifests (viakubectl apply). This is precisely the case for this operator as well. Find the installation methods available in the “Operator deployment on Kubernetes” section of their README file.Hi Dmitry

Spotahome operator uses sentinel model, when client connects to sentine service and client should be sentinel-ready.

Did you face any issues with this approach? What kind of redis library are you using?

Hi, Juri! Exact library usage depends on the customer’s infrastructure and language used. In some cases, we use redis-sentinel-proxy for libraries which aren’t able to use sentinel normally.

The problems that we get here usually aren’t technical, they lay mostly in the usual DevOps tasks, in teaching and assisting the developers how to better use the technology, how to optimize infrastructure. Because, as we can see in this post, the architecture problem is the cause of the overspent resources and failing Redises.

Hello! This article is very helpful! ?

I am curious if you are still using the operator from Spotahome or if you have considered/migrated to other options.

Not sure what were the options back in 2020 but currently there seem to be a few, such as the operator from [Opstree](https://github.com/ot-container-kit/redis-operator).

I am asking because the one from Opstree is also listed in OperatorHub while the one from Spotahome is not.

Hi Theodore!

Thank you!

We considered other options, including the one from Opstree you noted. However, as I recently mentioned in a comment above, we ended up using the Spotahome operator still in many deployments. It proved to be quite decent, after all. New releases are also happening to this date.

Hi.

You wrote you are planning to reconsider Spotahome’s use after analyzing the situation. Was this because of its shortcomings or because you needed Redis Cluster instead of Redis Sentinel? And which operator did you eventually land on?

Hi Sayed! We decided to reconsider it due to such shortcomings. However, the lessons were learned, and we had a positive experience in the end. This operator’s development was really stale for a while but revived later, and this project is a viable option. Thus we are still using it for numerous deployments even today. In some cases (when the cluster is needed), we prefer Redis Cluster, though.